Unexplainable Thoughts

- Jack Eureka

- Aug 8

- 4 min read

To reiterate, I know my methods of communication aren't great here, but my point is that it's all swirling around in my head in the few seconds between Dr. Lunderman's initial comment that it is "O.K." (which wasn't ever really asked nor did it need saying, in my non-doctored opinion) and his follow up explaining there is simply no way I could be a fraud. And so I really get nothing out in between, but he says that a real fraud wouldn't be able to sit in this very office and stare at him and say it out loud. They couldn't stare at him and admit it, he says.

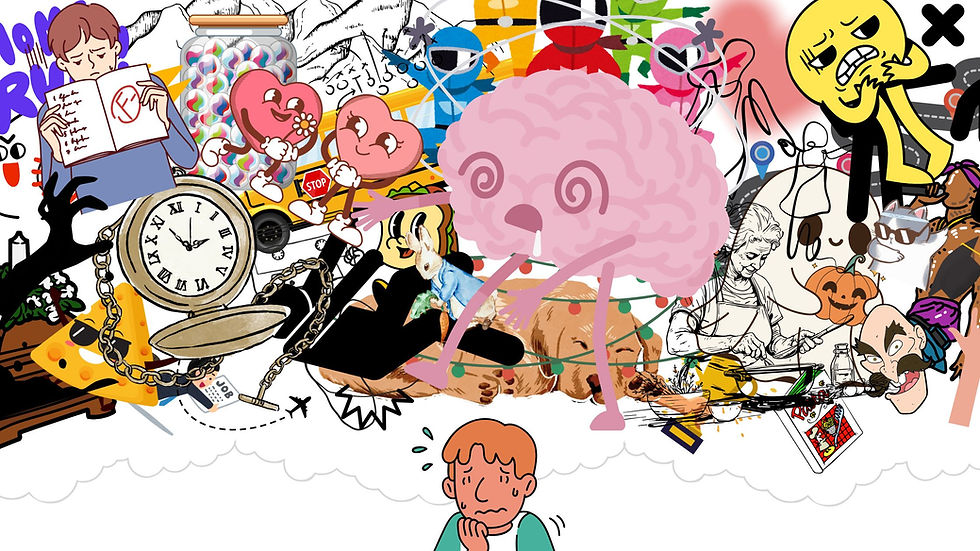

I know as well as he does how fast thoughts and associations fly through your head. You can be at work, or at a reunion, talking to a co-worker during lunch hour before returning to your duties, or watching your aunt who organized the reunion event make a speech. And during either, enough thoughts and feelings rush through your head — just in the breaths between words in these interactions — that they could all line up and stretch out in word and explanatory form to take on a distance of hours, weeks. Well past quitting time or cake clean up, and into the void of night. All of that worded distance crammed into the breaths between sentences. A constant and biblical flood of thought.

Which is the funny and unsolvable part. That so many of our best and prescient and smart thoughts or ideas come in these moments that are uncatchable. The nanoseconds between them a vacuum to another part of your brain that's far from memory. Divorced from our normal and retrievable ideas, like how to properly store cheese in the fridge, or what is the most optimal bedtime/sleep schedule for a person in your age bracket, or what that guy's real name was from Family Matters. In a separate language from our everyday communication and shorthand to one another. Even though for those split-seconds of bliss, nothing ever felt more lucid and abundant. And where the funny really and truly kicks in is when we (or I, in this office, staring at Dr. Lunderman right now) try and explain these thoughts and feelings to others, even though "explain" can't even really factor in. And then of course the other person tries to do the same, and we both realize in real time that what's coming out is not even close in word form to the speeding, brilliant form in our heads. And so we stare at each other, hollow-eyed and fake smiling, as these moments die on the cerebral vine. In that void between blinks. An inspirational and possibly life-changing thing that's sped up like a time-lapse at hyperspeed, sooner a ghost before the first thought of "I should say this out loud" even registers.

Maybe it's why we never say the things we're supposed to say. The things we think and feel at such a cellular level. They just never have the opportunity to come out.

When my grandfather (who was a perpetually awful and mean man his whole life) was dying, the entire family, from cousins to the fourth degree and aunts at a great- that requires subscript, came to his mansion of earned wealth in Massachusetts. This was a long time ago. I was just a kid, mind you. So mostly I remember being amazed at the size of his place compared to our Bed-Stuy apartment, and counting how many bathrooms there were, and how crazy it was that he had a butler like in the movies. But I also remember walking in with my mom. She was nervous and shaking, so I gripped her hand tight as we walked through what felt like hallway after hallway, and into an ornate room trimmed in gold. Which held at center, in a paper thin gown and unmoving, my grandfather — my mother's father. And then I stared at this old stranger covered in tubes, surrounded by digitized wavelengths and beeps. And she stared at him too and broke down, sobbing uncontrollably at this man who treated her like a social tax to earn more trust and get more money. Like an appeasement to his wife that could be treated (and would be treated) even worse as punishment for taking him from his work.

The old man stared back at her with eyes darting from hers to mine, glassy and knowing of the multitudes of apology and guilt bursting in his cells like synaptic popcorn. Seeing home movie-like reels of the pain he caused first-hand interstitched with the small moments he felt love for her, but never ever said out loud. Like when she opened a gift on her second birthday and looked up at him, smiling. Or when she fell asleep on the couch and he sternly told the butler "she's fine and she'll sleep there". But after which he then waited until the butler clocked out at midnight, and he picked her up in her cartoon-laden nightgown and carried her to bed. And then he stood there, staring at the sheer beauty of a sleeping child in the midnight light, just for a moment, before returning to the hallway and going to bed himself.

And then by morning it was gone.

As she sobbed at his deathbed's side, all these memories and moments hit at lightspeed in the old man's mind, and he stared at her open-mouthed, and he said nothing.